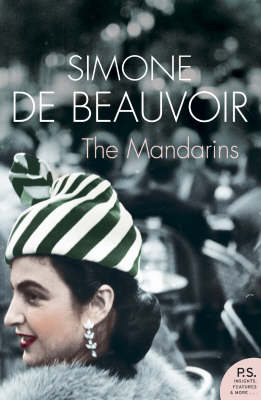

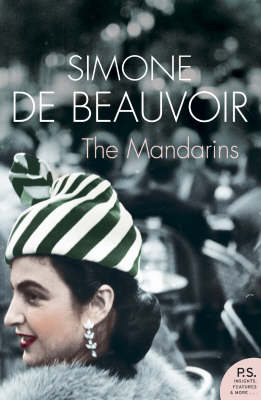

At over 700 pages long and filled with sweeping political and philosophical ideology and debates, not to mention a rather large cast of characters, this book won’t be easy to review! It was intimidating enough to simply read it.

At over 700 pages long and filled with sweeping political and philosophical ideology and debates, not to mention a rather large cast of characters, this book won’t be easy to review! It was intimidating enough to simply read it.

The story begins shortly after the liberation of France from German occupation in the Second World War. A group of friends, largely made up of notable Parisian intellectuals, are gathering at a celebratory party.

The party is thrown by Paula and Henri. The two have been together for ten years. Once passionately in love, the two now share a dysfunctional relationship. Paula, having given up her singing career, now devotes herself entirely to please and love Henri. Henri, the founder and editor of the independent newspaper, L’Espoir, no longer loves Paula but cannot leave her due to feelings of obligation and guilt. Having been a resistance fighter during the occupation, Henri is eager to assert his intellectual and physical freedom once more.

Henri’s best friend and mentor is Robert Drubreuilh, a university professor, who is now looking to enter politics with his socialist party, the SRL. His entire life is consumed with writing and politics. Robert’s wife Anne is a successful psychotherapist. She is twenty years younger than Robert and married him after a whirlwind romance while she was his student. The couple have one daughter, eighteen year-old Nadine, a surly and angry young girl. Anne and Nadine has always had a tempestuous relationship with Anne slightly resenting the interference of Nadine so early in her marriage. Similarly, Nadine resents Anne for competing with her for Robert’s attention. Still traumatised and angry after her lover is killed at a concentration camp, Nadine flits from one man to another. Anne, feeling unappreciated by her family and questioning her value as a psychotherapist to traumatised war victims, falls into an affair with an American writer.

The narrative alternates between Henri and Anne. All the characters struggle to place themselves in the new, post-war world and unable to reconcile who they once were and who they have become. The intellectuals also question their value and place in society and whether what they do make any difference any more or if they are simply just heard as empty words. As writers, Henri and Robert question their contribution to literature and if literature itself is worth anything anymore:

‘You [Robert] believe your major works are still ahead of you and just five minutes ago you said you were going to begin a new book. That implies that you believe there are people around who want to read what you’ve written…’

…

‘Oh, it’s not as horrible as you might think,’ [Robert] added cheerfully. ‘Literature is created for men and not men for literature’. – p. 55.

Anne, having been invited to a psychotherapist conference, wonders if it’s even worth learning new ideas or having new experiences anymore after the trauma the world and its people have just been through:

[Henri] gave me an encouraging smile. ‘You’re bound to make a few little discoveries, but I’d be very much surprised if they upset your whole life. The things that happen to us or the things we do, they’re never really so important in the end.’

I bowed my head. ‘It’s true,’ I thought. ‘Things always turn out to be less important than I thought they’d be. I’ll leave, I’ll return; everything comes to an end and nothing ever happens.’ – p. 251

Whatever one does, things will always stay the same while nothing will ever remain as they were (!), or as the other and more eloquent saying goes, the more things change the more they stay the same.

Known as the defining figure of feminism, it always surprises me that de Beauvoir writes such frustrating female characters. As in She Came to Stay, in this book both Paula and Nadine (and to a lesser extent, Anne) are unbelievably frustrating women, particularly Paula. This woman devotes herself to Henri’s existence and deludes herself into thinking that nothing has changed in their relationship. She comes up with elaborate excuses for Henri’s behaviour and whatever he does, she excuses it and turns the blame onto herself:

‘Above all, don’t apologize!’ She looked up at him, her face trembling with humility. ‘The night of the opening and in the days that followed, I came to understand a great many things. There’s no standard by which you can be measured against other people, against me. To want you as I had dreamed of you and not as you are was to prefer myself to you. It was pure presumptuousness. But that’s over. There’s only you; I’m nothing. I accept being nothing, and I’ll accept anything from you.’ – p. 486

To be clear, Henri is not a horrible man nor does he treat Paula badly which makes Paula’s obstinacy and emotional blackmail all the more hateful. Of course, Paula’s situation can be somewhat understood. Having been with Henri in the prime of life and having given everything to him and the relationship, Paula is only trying salvage any semblance of the only life that she now knows.

Nadine, on the other hand, is more understandable and perhaps symbolic of a generation. She is bitter, angry and suspicious at the world, having had her first love and innocence ripped away from her due to simply being the victim of circumstances. She cannot understand the world, its violence and ideals. While her cruelness is a way for Nadine to cope, I did find this a rather admirable skill:

He grabbed her by the wrists. When [Anne] finally reached them, he was so pale that I thought he would faint. Nadine’s nose was bleeding, but I knew she could make her nose bleed at will – it was a trick she had learned during her childhood when she would with her playmates around the fountains of the Jardin du Luxembourg. – p. 456

This review, of course, is really only a general outline but the over arching theme is the eternal struggle of finding one’s place in the world, particularly the post-war world where everything has changed and once unthinkable acts carried out. The meaning of their actions during their life and the worth of its impact, if any, and if anything the characters do matter at all in the end:

‘First of all, it’s important that suicide be difficult,’ Robert said. ‘And then continuing to live isn’t only continuing to breathe. No one ever succeeds in settling down in complete apathy. You like certain things, you hate others, you become indignant, you admire – all of which implies that you recognize the values of life.’ -p. 433

The book was a great read. While it get fairly political in some points (it’s so strange reading the kudos of communist Russia) it never gets boring or slow. In fact, time often flew while I was reading it! There is also the more infamous autobiographical notes in the novel widely understood to be modelled on de Beauvoir, Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus (whose character I correctly guessed) and Nelson Algren to whom the book is dedicated to.

I suppose the title says it all really, as well as the cover art which is sparkly gold. The debut novel from Singaporean native Kevin Kwan is a funny, light and enjoying read. Set largely in Singapore, the novel follows the rich and famous as they descend into the small island country for the wedding of the year – the son of one of the richest families marrying a famous model whose family comes from ‘new’ money. We follow Nicholas Young who, having been educated overseas and is now an up-and-coming professor at Stanford University, invites his ABC (American Bord Chinese) girlfriend Rachael to Singapore for the wedding and to meet his family. Away from the craziness of his insanely wealthy family and extended family, Nick innocently lures Rachel into a minefield of cattiness and snobbery of the highest kind (coming from Mainland China is the biggest sin of all). The novel is filled with couture clothing totalling over millions, lots of private jets and first class flying, penny pinching, penthouses, royal Thai-maids, Gurkhas and other expensive frivolities that makes you hope that excesses such as these are not actually real.

I suppose the title says it all really, as well as the cover art which is sparkly gold. The debut novel from Singaporean native Kevin Kwan is a funny, light and enjoying read. Set largely in Singapore, the novel follows the rich and famous as they descend into the small island country for the wedding of the year – the son of one of the richest families marrying a famous model whose family comes from ‘new’ money. We follow Nicholas Young who, having been educated overseas and is now an up-and-coming professor at Stanford University, invites his ABC (American Bord Chinese) girlfriend Rachael to Singapore for the wedding and to meet his family. Away from the craziness of his insanely wealthy family and extended family, Nick innocently lures Rachel into a minefield of cattiness and snobbery of the highest kind (coming from Mainland China is the biggest sin of all). The novel is filled with couture clothing totalling over millions, lots of private jets and first class flying, penny pinching, penthouses, royal Thai-maids, Gurkhas and other expensive frivolities that makes you hope that excesses such as these are not actually real.